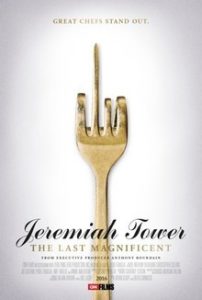

“Jeremiah Tower: The Last Magnificent” Downplays a Deserving STAR

(Gerry Furth-Sides) “Star” chef, Jeremiah Tower, the subject of Jeremiah Tower: The Last Magnificent in every way deserves this film tribute, although in a much more fair depiction.

(Gerry Furth-Sides) “Star” chef, Jeremiah Tower, the subject of Jeremiah Tower: The Last Magnificent in every way deserves this film tribute, although in a much more fair depiction.

The film was named after the chef’s own hero, Lucius Beebe, described as “The Last Magnifico” in James Villas’ Gourmet profile. Tall, tan and handsome, Tower remains not only a food legend from a pre-celebrity-saturated era but possibly the first to be labeled, “super chef.”

Executive-produced by long-time fan, Anthony Bourdain the film provokes a dash to the internet and a read of the Towers’ books. Bourdain is this generation’s Jeremiah Tower, welcoming his viewers into diverse, culinary adventures around the world.

I could not put down California Dish, What I Saw (and Cooked) at the American Culinary Revolution. The book should be required reading for every chef. I could spend a semester on his thoughtful bibliography after looking up at least one name or concept in each chapter.

Directed by Lydia Tenaglia, the film feebly gets the storyline right. That is, Chef Tower is the classic case of the right person at the right time as the chef who ensured the good fortunes of Chez Panisse chef to afterward open Stars restaurant in San Francisco, and later the wrong person when there never was a good time at Tavern on the Green in New York.

With Chez Panisse and Stars, Chef Tower ushered American Cuisine into the culinary lexicon in grand style, both farm-to-table and making “stars” of regional ingredients. Thus the talking-head praise of colleagues is in perfect order. But more footage of the chef at work, please! There is plenty to go around since Tower was one of the first chefs to use outside media events to promote his restaurant.

The names Stars and Chez Panisse were legendary in the early 80’s just through the “buzz” in those pre-internet days. Chez Panisse literally made famous the concept of an open kitchen and farm-to-table fresh ingredients listed on the menu.

When Jeremiah Towers opened Stars in San Francisco, he realized his own dream of creating the atmosphere he found on the luxury liner ships, trains, hotels and restaurants he had loved as a lonely child. He was at home as both a front-of-the house and back-of-the house master. What he didn’t have was a Barbara Lazaroff to his Wolfgang Puck to handle the financial end of things of what became his international empire, much to his later demise. Yet he was an astute strategist even on his own.

Yet where Wolfgang Puck would be just as happy cooking over a stove as doing anything else in a restaurant, Jeremiah was the consummate happy host. As Mario Batali underscores describing Chef Tower’s mastery of restaurants, “No one understands the relationship between chef and diner like Tower.” Tower created restaurant after restaurant after that with just as much success, if not acclaim.

Yet where Wolfgang Puck would be just as happy cooking over a stove as doing anything else in a restaurant, Jeremiah was the consummate happy host. As Mario Batali underscores describing Chef Tower’s mastery of restaurants, “No one understands the relationship between chef and diner like Tower.” Tower created restaurant after restaurant after that with just as much success, if not acclaim.

The restaurant held up as at least the more sophisticated equivalent of brash Studio 54, New York glitter of decades earlier — socialites giddily mixing it up with rock stars – but this time with piano playing softly in the Stars background and the best food in the world.

When we couldn’t get a last-minute table on a Friday night visit, we were royally ushered to front row people-watching seats at the kitchen pass-through and the priceless opportunity to eat their famous $3.50 hot dog. It was as much fun as the dinner another time.

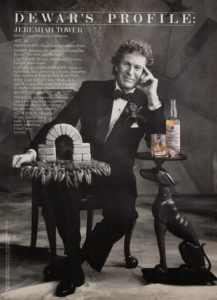

At the time, Chef Tower was at the height of his fame (see the full-page Dewar’s scotch profile of the glamourous chef that appeared in slick magazines above). Still he was the most approachable and lovely man in person. When I phoned him at Stars with an invite to our national seafood competition , he answered the phone himself and carefully explained to me his conflict of schedules and regrets that made me feel he was more disappointed than I ever could be.

Towers’ remarkable talent, expertise and education as an architecture enabled him to realize his ambitious vision of Stars – nicely portrayed in the film. As a college student, Tower already prepared sumptuous meals for lucky diners inspired by the scores of his beloved menus he had collected from the finest restaurants around the world.

Jeremiah Tower: The Last Magnificent film instead portrays him as sort of “dabbling” at architecture. The film only begins, (begins!) exploring his astonishing creative process as he renews very old homes in Mexico, and and how they “speak to him.” It also completely leaves out his lifelong fascination with the lost Atlantis, which in a way propelled him into a culinary career after his Atlantis-type underwater construction project was rebuffed. Instead the film makes his love of Mexico and snorkeling into a murky mystery, which it is not at all.

A comparison of the creativity in his architecture and culinary passions would have perhaps been a better hook to the film than him as an the enigmatic loner, here explained in stilted dramatizations. True, Tower has the slightly crazy mind of an architect who uses both left and right brain, meticulous and patrician, yet retaining a youthful artistic and visionary energy. The film paints him as just plain weird.

Instead, Chef Tower is so totally approachable. He has the grace and gift of the upper class to make people feel comfortable. And, in his case, the burning desire to include everyone into his party.

Instead, Chef Tower is so totally approachable. He has the grace and gift of the upper class to make people feel comfortable. And, in his case, the burning desire to include everyone into his party.

In fact the reason for his fame was that everything he created in his restaurant expressed his love in the form of elegant hospitality, the ritual of the meal. And in Tower’s version of elevated dining with his French interpretation of dishes prepared with California ingredients he singled out with pride on his menus for the first time in a cosmopolitan restaurant.

In fact the reason for his fame was that everything he created in his restaurant expressed his love in the form of elegant hospitality, the ritual of the meal. And in Tower’s version of elevated dining with his French interpretation of dishes prepared with California ingredients he singled out with pride on his menus for the first time in a cosmopolitan restaurant.

It was a practice he developed working at Chez Panisse in Berkeley with Alice Waters, where they served as each other’s muses and the romanticist Waters chased the then close-to-beautiful (gay) Tower successfully around the kitchen and not so much so in the bedroom –which may or may not have led to a petulant Waters leaving Towers out of the Chez Panisse cookbook and him leaving in 1978. Chef Towers quiet, sincere explanation of the situation in the film is one worth the price of admission.

It was a practice he developed working at Chez Panisse in Berkeley with Alice Waters, where they served as each other’s muses and the romanticist Waters chased the then close-to-beautiful (gay) Tower successfully around the kitchen and not so much so in the bedroom –which may or may not have led to a petulant Waters leaving Towers out of the Chez Panisse cookbook and him leaving in 1978. Chef Towers quiet, sincere explanation of the situation in the film is one worth the price of admission.

Jeremiah Tower: The Last Magnificent answers only the surface important questions as it winds up in more linear fashion about the demise of STARS and the illusiveness of the chef after that — namely “the stars” being in all the wrong places for Tower at once with the San Francisco earthquake that demolished the restaurant and its city hall neighborhood clientele; a misunderstood law suit that painted Tower as anti-gay when in fact he was a supporter of gay rights.

It concludes with marvelous footage of Chef Jeremiah Tower coming out of seclusion to head up the Tavern on the Green Restaurant in New York — which Anthony Bourdain describes as a “chef killer” that also pretty much describes the outcome.  It is beautifully filmed in the wintery, snowy hush of Central Park. Here we see firsthand the detailed vision of a brilliantly talented, successful and competent chef disintegrate before our eyes in a corporate world where the object is to feed high-end, walk-in customers on a daily basis.

It is beautifully filmed in the wintery, snowy hush of Central Park. Here we see firsthand the detailed vision of a brilliantly talented, successful and competent chef disintegrate before our eyes in a corporate world where the object is to feed high-end, walk-in customers on a daily basis.

Perhaps the sequel to the film will be, in fact, architect Jeremiah Tower’s underwater project realized after all. We salute him and wish him the best.

Perhaps the sequel to the film will be, in fact, architect Jeremiah Tower’s underwater project realized after all. We salute him and wish him the best.

“Jeremiah Tower: The Last Magnificent”

Rating: R for language.

Running time: 1 hour, 42 minutes.

Playing Landmark, West Los Angeles.

Gerry Furth-Sides

Gerry Furth-Sides  Barbara Hansen

Barbara Hansen  Chef-owner Alain Cohen

Chef-owner Alain Cohen  Roberta Deen

Roberta Deen  Jose Martinez

Jose Martinez  Nivedita Basu

Nivedita Basu