Astonishing Georgian Wines Keep “Georgia on My Mind”

(Gerry Furth-Sides) “Georgia on my Mind” – this Georgia being the small country in the Caucasus region known for being the first winemakers in the world and where producers still use ancient “qvevri” (meaning underground) clay pots that make them the most exciting recent find of wine experts everywhere.

In a way, it could be compared to the world eating only sauerkraut and all of a sudden learning about ancient Korean Kim chi cabbage, also fermented in pots.

We agree wholeheartedly after a presentation of four indigenous varietals of Georgia’s 525 at Republique about this ancient find that has the international wine world abuzz.

We were impressed from the first Schuchmann, Mtsvane 2014, which was surprisingly clean, clear (after being told about the cloudy whites, stainless steel vinification) and refreshing all the way. Hints of citrusy lemon and light orange on the nose are followed by layers of lingering sweet grapefruit, orange zest, and lemon curd, with a solid medium finish.

Renowned, sommelier, Taylor Parsons (Whole Cluster beverage and wine consultant, former Republique Wine Director) and Los Angeles Times wine writer, Patrick Comiskey led the seminar, pretty much breathless with excitement, stopping often to show their personal slides of the winemakers and unusual methods.

Renowned, sommelier, Taylor Parsons (Whole Cluster beverage and wine consultant, former Republique Wine Director) and Los Angeles Times wine writer, Patrick Comiskey led the seminar, pretty much breathless with excitement, stopping often to show their personal slides of the winemakers and unusual methods.

Wine expert Taylor Parsons double checks the wine list.

Why now? After all the Bible says Noah planted a vineyard nearby after the ark settled on Mount Ararat. Georgian representatives and International wine news have been allowed out only recently although Georgia is known as “the cradle of wine” for its uninterrupted, 8,000-year winemaking history. Now considered such a treasure, the giant qvevri are now UNESCO protected.

Georgia’s history and topography ranging from lush to Savannah, almost desert, Taylor told us. This is where ancient trade routes crisscrossed the mountains between the Black Sea and Persia, inviting continuous invasions by other countries ever since the Middle Ages.

Georgia’s history and topography ranging from lush to Savannah, almost desert, Taylor told us. This is where ancient trade routes crisscrossed the mountains between the Black Sea and Persia, inviting continuous invasions by other countries ever since the Middle Ages.

Leave it to the stalwart Georgian personality in adverse conditions. Not only did farmers secret away a few vines each time invaders ripped out orchards, but they lovingly tended them in their backyards, improving them along the way. Then, adding insult to injury, 70 years ago the Soviet Union government limited farmers to growing only two grapes (Rkatsiteli and saperavi), adding a proviso that only sweet wines would be allowed for the commercial Russian market. All this is over now.

Although Georgia is at the heart of the Europe and Asia, Parsons described Georgian wines as taking on eastern rather than western characteristics, more like preserves or an Asian fermenting process than French wines to the west, known for their fruit flavors.

However, French wines, Georgian wines are usually a blend of two or more grapes. They are classified as sweet, semi-sweet, semi-dry, dry, fortified and sparkling. The semi-sweet varieties are the most popular.

The fermenting process is a natural one, usually with skins and seeds, and sometimes even includes stems along with the juice. The resulting flavors of the qvevri transform of them into textural wines texturally experience as well, what Parsons kept emphasizing over and over, “are unlike any others in wine.”

Saperavi (reds) and Tsolikouri, Mtsvane and Rkatsiteli (whites) provided a wonderful introduction to the wines after the Schuchmann, Mtsvane 2014.

Red wines are the familiar shades of purple, ruby, garnet, and purple. Georgia is best known for Saperavi, a black-fruited, tannic and sometimes powerful red. The name means ” to dye” because the juice of the red grapes is additionally tinted.

Georgians favor a variety of whites from their indigenous grapes. Parsons was surprised that some winemakers process white wines like red wines, macerating them on their skins, with or without stems, and for various amount of time. This is also what prompts the tannins in the white wines, admittedly, he concluded, “some more successful than others in taste.” Unfiltered, their sort of foggy look can be offputting.

Georgians favor a variety of whites from their indigenous grapes. Parsons was surprised that some winemakers process white wines like red wines, macerating them on their skins, with or without stems, and for various amount of time. This is also what prompts the tannins in the white wines, admittedly, he concluded, “some more successful than others in taste.” Unfiltered, their sort of foggy look can be offputting.

Instead of the bright lemon or golden colors of white wines, Georgian white wines can range in color from yellow and golden to gentle peach and orange. The amber-colored whites (truly the color you associate with the resin) is weighty with acid and tannin that flood the palate.

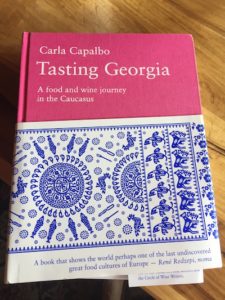

These are all wines that enhance food, due to their acidity and tannin. And in Georgia, the versatile wines are served with every sort of food from cheeses and fruits to grilled meats and vegetables. Cookbooks celebrating Georgian food are just now arriving in bookstores.

Georgian hosts allowing a whopping 2.5 liters per guest (though only 10-13% alcohol). I’ve been a guest in a Russian home and parties always lasted from noon to midnight with lots of food – always one absorbing potato dish – to fully appreciate this allotment. We tried the ORGO Rkatsiteli 2014, a dry amber wine from Old Vineyards on an Indian summer day, perfect since it is described as “the Eternity of the sun Living in a Bottle.” The Rkatsiteli grape variety has a home in the Kakheti region of the country. It is a delightful example of the qvevri fermentation method; on the bottle, it explains that the “amber color is a result of its extended contact with the skins.”

We tried the ORGO Rkatsiteli 2014, a dry amber wine from Old Vineyards on an Indian summer day, perfect since it is described as “the Eternity of the sun Living in a Bottle.” The Rkatsiteli grape variety has a home in the Kakheti region of the country. It is a delightful example of the qvevri fermentation method; on the bottle, it explains that the “amber color is a result of its extended contact with the skins.”

We served it with a salmon salad, broccoli slaw, and a baguette. Each enhanced the flavors of the other with the wine’s notes of dried apple and apricots, followed by a lingering taste of sweet spices and dried herbs. It is also recommended to be served with grilled pork and creamy pasta — we will next time!

Georgia’s dramatic variety in a landscape is matched by the wide array of winemakers. While the list of vintages is 8,000 the list of winemakers is short, tending to be either small family-run affairs or huge enterprises. Even descriptions of the winemakers themselves lend themselves to flights of quickly fancy: “The Scientist & the Visionary; The Craftsman & the Tinkerer; the Rebel & the Farmer”. While the majority of the wineries produce 2,000-3,000 bottles per year, less than ten wineries produce seven million bottles annually.

Georgia’s dramatic variety in a landscape is matched by the wide array of winemakers. While the list of vintages is 8,000 the list of winemakers is short, tending to be either small family-run affairs or huge enterprises. Even descriptions of the winemakers themselves lend themselves to flights of quickly fancy: “The Scientist & the Visionary; The Craftsman & the Tinkerer; the Rebel & the Farmer”. While the majority of the wineries produce 2,000-3,000 bottles per year, less than ten wineries produce seven million bottles annually.

And, in the end, there is indeed a tie between the two “Georgia’s.” Georgia, in ancient Greek georgos, originated as an admiring appellation for a farmer. Romans spread the name into Western European languages, where it became used for Christian saint and kings. Centuries later, as was common at the time, when the land to the south of South Carolina was being established as a penal colony, the new colony was named in honor of the reigning monarch, King George, in a Latinized form: Georgia.

Gerry Furth-Sides

Gerry Furth-Sides  Barbara Hansen

Barbara Hansen  Chef-owner Alain Cohen

Chef-owner Alain Cohen  Roberta Deen

Roberta Deen  Jose Martinez

Jose Martinez  Nivedita Basu

Nivedita Basu