Star Chef Toribio Prado’s Meteoric Career

Chef Toribio Prado, a meteoric force that changed the LA culinary scene is gone forever at the age of 54.

We last watched him “slinging tacos” from a food court overlooking the famous restaurant he first brought to fame with his menu, still intact, at the age of 17.

Chef Toribio Prado, a meteoric force that changed the LA culinary scene is gone forever at the age of 54.

We last watched him “slinging tacos” from a food court overlooking the famous restaurant he first brought to fame with his menu, still intact, at the age of 17.

The restaurant is the historic Ivy at the Shore. Toribio’s family stayed in both this location and original Ivy Restaurant, cooking that menu until they retired or opened their own places, often backed by Toribio.

The tacos are of a multi-unit company Pinchas Tacos, owned by his nephews, who learned the business working for him. They were part of the extended family that staffed Cha Cha Cha and Cava restaurants across the city.

And only a few blocks away in Santa Monica at the end of Pico sits one of the two successful Cha Cha Chicken Cafes – which I inspired, and which have given a business career to his three beautiful children.

This creation alone showed the motivation and determination of Toribio; our friend, Deno Andrianos, who owned four Astro-burgers with his partners at the time, had looked over the site and said it was “too dilapidated, dirty and desolate a location” for him to consider.

The chef was not new to overcoming such circumstances. His story, in fact, begins in Michoacan, Mexico with a childhood happy only in the kitchen. As Toribio himself told it, he was the 10th of 14 children, “born with a spoon in my hand ‘an I cooked for my brothers and sisters since I was four. He would chuckle in his gravelly voice, “this spoon was silver; so means I also never have to clean up.”

Because he was “different,” his father kept him away from school. Riding behind his mom on horseback and by her side in the kitchen, Toribio learned the fine art of choosing ingredients and preparing dishes handed down through the family for generations. But he did not learn reading or writing until he learned on his own – sort of.

That he left home because his dad cut off his ponytail while he was asleep is a story that never varies. But Toribio’s own version of where he grew up ranges wildly from Cuba (and hie Che beret perfected it), to living in European capitals with his famous, traveling architect father. As for his story of being a personal chef and nanny to actress Sophia Loren’s children…

Then there is the matter of Toribo listing his job as Hugo’s Restaurant “culinary consultant” before arriving on the scene to create the Ivy’s opening menu. But ask Hugo’s owner, Terri Kaplan, and he laughs. “Toribio was a polite, very quiet, hard-working young busboy,” he recalled to me. “But I didn’t know he cooked! believe me I would have loved him cooking in the kitchen for Hugo’s.”

Thus, everything in Toribio’s memory seemed to edge up on but never quite touch reality. But no one cared because his cooking was so inspired, and imaginative, talented, generous, funny, original and candid rascal he took such joy in sharing all of it with whoever was around.

Earnest, sophisticated, childlike – along with a flair for cutting edge fashion – earned Toribio a Buzz magazine honor of “one of the 100 coolest people in the city.”

The true Ivy story. When George Christie convinced Lyon von Kersting and Richard Irving to expand their bakery concept into a restaurant, they needed a chef. Toribio arrived on the scene at a private holiday dinner minus a chef, and convinced them to let him try his hand.

And so the Ivy became a reality, and an immediate star. Lynn’s inviting, southern belle decor and hand-painted dishes, Richard’s baked goods and Prado’s food attracted immediate local and national attention. It became an instant celebrity and food critic favorite – including a young John Travolta who picked up his meal everyday.

Ironically the original Ivy Restaurant was featured in the film, “Get Shorty” starring Travolta. But in the Ivy scene, it was“film star” Danny DeVito who ordered a dish “off the menu.” Toribio would roar at this turn of events.

At a time where French cuisine reigned in Los Angeles, Prado introduced Cajun and Creole seasons at the Ivy, with tropical fruits and cooking techniques from South America and the Caribbean.

For decades, his heavenly little round loaf of Anadama bread on each table, along with crabcakes, dill salad and aoli was the perfect meal. He claimed he learned how to make that bread from a family in New Orleans who took him in (in a driving rain storm, of course) on a research trip funded by Lynn and Richard.

Even with Lynn’s brilliant, inviting sort of American South-South American “veranda” atmosphere that complemented his food so beautifully, Toribio grew restless with the upscale, structured atmosphere. (Lynne posting restaurant reviews featuring the young chef in the restrooms was not quite so posh).

So with hairdresser partner Mario Tamayo, he opened the first Cha Cha Cha restaurant on an isolated patch of an eastside Silverlake corner field in 1986. The extraordinary Pan Caribbean food and outrageously colorful décor in a rambunctious party atmosphere catapulted it immediately into stardom.

Ruth Reichl Los Angeles Times: “The evening featured Jamaican curries, Serrano chilies, Lobster moles, and the Caribbean spices that were new, exotic, and dangerous – the early forays of a culinary pioneer.”

Lynell George wrote in Los Angeles Times: Cha Cha Cha is “a jubilant dinner party in progress, filling the air with a host of enticements-citrus, garlic, and nose-itching chilies.”

Years later I convinced Lynell to write the family’s story which turned into a two-page spread in the LA Times. We spent the week-end at Toribio’s home in Vista (which he claimed was Hillcrest, of course). I didn’t know whether to expect – cabin or castle- and it turned out to be a sort of the latter, aa sandcastle to be sure, filled with wonderful, whimsical artwork by Toribio and his friends. The week-end went this way: Eating a luscious breakfast while Toribio dreamt up lunch; lunch with Toribio planning dinner, with a pulled pork dish centerpiece that I remember to this day.

Toribio presided as Lord of the manor, and all was served up in grand style. It reminded me of the evenings of research we had at outside restaurants. After one six-course meal at the new Il Grano, Toribio leaned back with satisfaction. I asked his thoughts. “Couldn’t he have served the whole fish on bamboo – why aluminum foil?” summed up the experience for him.

It reminded me of an evening as the honored guests at the House of Blues Foundation room, where Toribio wove a garland treat of flowers for my hair — out of the centerpiece. But, as always, when I returned home after being with him, the phone rang, and it was him thanking me sincerely and warmly for such a wonderful evening.

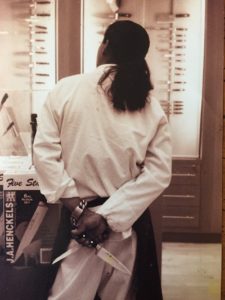

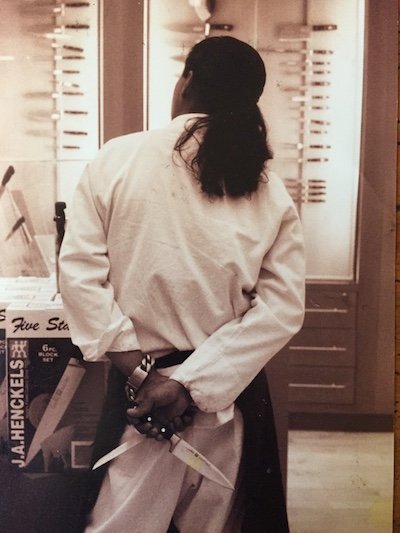

Toribio’s demons started chasing him almost full time by then but he arrived at the photo shoot to sit on his peacock chair in the middle wearing his then-signature, very regal, purple velveteen suit and ever-present pony tail.

A partner dispute separated Prado and Tamayo, Toribio taking the Cha Cha Cha name and Tamayo the Mambo restaurant a few blocks away. By the late 1980’s, Cha Cha Cha had three locations in Long Beach, Encino and San Francisco, as well as the more upscale Cava through the 90’s.

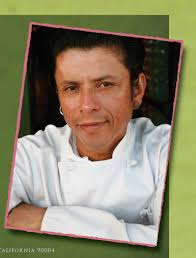

Cava. At the end of 1998 I was called upon by the national Onion Commission to help them promote Peruvian onions. I helped them arrange a Hollywood Boulevard parade, complete with flute band and burro, and afterward a media lunch at CAVA, where Toribio outdid himself . Margaret Sheridan of the spectacular meal and the chef’s bracelets in the LA TIMES, “Toribio had more chains on than a ski resort parking lot in winter.”

It was also at Cava that I had the bright idea of doing a Sephardic sedar, probably the first in an LA restaurant. Karen and Michael Berk brought all the religious elements (and guests), and Michael officiated. And Toribio’s meals both years were masterpieces we will remember forever, and a new way at the time of looking at Jewish holiday food.

In 1999, The James Beard Foundation honored Toribio with a personal invitation to cook at the New York City home of Mr. Beard. I was the one who arranged this. All went well at the rehearsal media dinner at CAVA in LA. A rum mojito from a sponsor started off the meal. What we didn’t quite plan on in New York was a rum cocktail with each course – so everyone had a grand time at the dinner but I’m not so sure how much any remembered after the second course.

When we walked out to the after-party, we came upon this sidewalk art that summer it all up:

But that angel continued to fall even through Toribio teaching cooking classes at Vista Del Mar Home for Children. And in 2001 the gritty “The Fast and the Furious” fittingly shot a scene at the original Cha Cha Cha. Frustrated at the time its meaning seemed to be following me when I recognized it even with its low lighting. The screen notes now read: “Cha Cha Cha is an actual L.A. restaurant (and a quite popular one), serving Caribbean food in a colorful atmosphere… in a questionable neighborhood”.

The Anaya nephews bought the place in 2003 and celebrated its twenty-year anniversary in 2006. The entire street was shut down and Los Angeles City Council honored it with a commendation, declaring the day, “Cha Cha Cha Day in Los Angeles.’

Toribio joined in, wearing a wild costume of horsehair chaps. And as the “Fast and the Furious” scene found me, so did these little chaps on a door yesterday in a restaurant.

Only a few years later it was leveled; today there is no trace of it ever existing, and no Toribio. Still, his legacy of refined ethnic Caribbean cuisine, along with the energy of so so many stellar food and party memories, is so strong that I’m sure he’s up there somewhere, chuckling and sharing them, too.

Gerry Furth-Sides

Gerry Furth-Sides  Barbara Hansen

Barbara Hansen  Chef-owner Alain Cohen

Chef-owner Alain Cohen  Roberta Deen

Roberta Deen  Jose Martinez

Jose Martinez  Nivedita Basu

Nivedita Basu