How “King of the Yees” Explores Chinese Culinary Lore

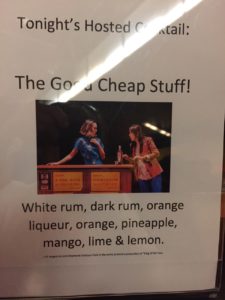

Chinese Fortune Cookies, oranges and “the Best of the Cheap Stuff” alcohol play a prominent part in the production of Lauren Yee’s “King of the Yees”. Our heroine must produce them in order to rescue her father. The play is a lively reminder of how Asian cultures are rich with symbolism.

“King of the Yees” is directed by Joshua Kahan Brody and produced in association with Goodman Theatre. The play continues its run in other cities as a lively work in progress.

“King of the Yees” is directed by Joshua Kahan Brody and produced in association with Goodman Theatre. The play continues its run in other cities as a lively work in progress.

We saw a performance at the Center Theatre Group’s Kirk Douglas Theatre where the entire theatre was the stage met with great audience approval.

The extraordinarily lively, elastic cast also seemed to thoroughly enjoy every minute of the play, with each member adroitly played multiple parts. The case in alphabetical order included Rammel Chan, Francis Jue, Angela Lin, Stephenie Soohyun Park and Daniel Smith.

The extraordinarily lively, elastic cast also seemed to thoroughly enjoy every minute of the play, with each member adroitly played multiple parts. The case in alphabetical order included Rammel Chan, Francis Jue, Angela Lin, Stephenie Soohyun Park and Daniel Smith.

For nearly 20 years, playwright Lauren Yee’s ambitious father, Larry, has been a driving force in the 150 all-male Yee Family Association. But when her father goes missing at a meeting, Lauren plunges into the surreal, circular “rabbit hole” of San Francisco’s Chinatown to rescue him in “King of the Yees”

Linguist Noam Chomsky fittingly tells us, the Chinese style of language is circular, with thoughts running in a spiral fashion. The speaker getting to the point in the middle of the shell. It’s similar to the old-fashioned circular hopscotch game made of boxes. Every time you made it to the middle without stepping on a line, you claimed a box the other players then had to jump over.

King of the Yees also moves Lauren in a spiral having to jump over boxes marked for others. The name and the meaning of family ancestry are at the core of her own Chinese puzzle. Here are the details in the author’s own words.

//www.onstage.goodmantheatre.org/2017/03/20/meet-the-playwright-a-conversation-with-lauren-yee/

There was a slight tug at my heart when Ms. Yee was reading off a list of things “San Francisco” pertaining to this– including Waverly Place – the street that the Amy Tan character was named after in The Joy Luck Club.

Chinatown in the Lauren’s ’70’s was “the most densely populated urban area west of Manhattan, with the oldest and poorest residents who only spoke Chinese. Close to 15,000 residents lived in 20 square blocks, the population density seven times the San Francisco average. By 2000 it had grown to over 100,000.

During those times tong means a Chinese organization “hall” or “gathering place, really secret societies of sworn brotherhoods often with affiliations to Chinese crime gangs. Current tongs are productive associations that provide community services. They can be traced back to the Kuomintang in China, forced into secrecy once the Communists took power.

The set, which comes alive in different ways throughout the production is truly remarkable, including looking at it up close.

The set, which comes alive in different ways throughout the production is truly remarkable, including looking at it up close.

What are the meanings of the symbols in the play? The orange is a prayer or wishes for good fortune. Oranges are used in temple offerings and the harvest festival because they symbolize life and a new beginning. The Chinese are known to love fruits, especially big and beautiful, and fresh.

Sugared oranges are a wish for a sweet year and are eaten on the second day of the New Year because an Emperor once distributed oranges to his officials on this day. Thus oranges on this occasion translate into a wish for officialdom when eaten on this day.

Oranges also become offers of good wishes when they accompany Chinese New Year gifts and appear as party table decoration. Leaf-on proves its freshness and fond wishes.

A bride is given two oranges by her new in-laws, to peel and share with her husband on their wedding day. They symbolize a family wish for the couple to share a full and happy life.

The popular fortune cookie, have come to be an expected American dessert in Chinese restaurants. The crisp and not very sweet tiny tuille includes sesame seed oil, which lends it an “Asian taste” . A small piece of paper with a “fortune” on it is tucked inside, usually with a witty aphorism or prophecy, plus a list of lucky numbers. Whether urban legend or true, some numbers have been reported to have become actual winning ones.

The exact origin of fortune cookies is unclear though it was definitely not in China. Most likely they originated from cookies made by Japanese immigrants to the United States around the turn of the 20th century as part of their tea ceremony (minus the lucky numbers!) The theories about its origin were so controversial that in 1983, there was even a mock trial held in San Francisco’s pseudo-legal Court of Historical Review to determine the origins of the fortune cookie!

When it comes to the “best of the cheap stuff, ” honored in a reception cocktail, the Chinese know no rival. They are known to be concerned with quality and cheap price and drive a hard bargain. Amy Tan described this so beautifully in Joy Luck Club, where “quality” ingredients were the requirements for a good life in America.

Now the studies have proven this true. First, it was determined that for Chinese shoppers find pleasure in shopping research and shopping, In a recent survey, 68 percent of Chinese respondents answered they were “happy or overjoyed” with their shopping experiences, in the three key phases of the shopping experience—“being inspired, having fun, and learning something”—compared to 48 percent of American respondents and 41 percent of British respondents.

For more information, please see: //www.centertheatregroup.org/about/press-room/press-releases-and-photos/archive/2017/july/king-of-the-yees-opens-at-the-kirk-douglas-theatre/

Gerry Furth-Sides

Gerry Furth-Sides  Barbara Hansen

Barbara Hansen  Chef-owner Alain Cohen

Chef-owner Alain Cohen  Roberta Deen

Roberta Deen  Jose Martinez

Jose Martinez  Nivedita Basu

Nivedita Basu