“Save the Deli” Book: International Jewish Soul Food

(Gerry Furth-Sides) In his plea to “save this institution,” David Sax’s book, Save the Deli becomes the definitive account of delis around the world. Besides providing detailed, mouth-watering descriptions of the food he is served in his exhaustive research – along with witty accounts of the folks who prepare it – the author expertly serves up its cultural history. As a critical fan of such memoir-histories, Sax ranks right up there with Anthony Bourdain (Kitchen Confidential), Bill Buford (Heat) and Mark Kurlansky (Salt), all books I highly recommend for gift or home bookshelf.

With Save the Deli I additionally compare his research with my own deli notes albeit mine mostly on pastrami and corn beef sandwiches. He includes the very same accounting of how pastrami came to America via Gussman Volk because he accepted a recipe for pastrami (noting the term “pastrami” as noun or verb) in return for watching the suitcase of a neighbor while he was traveling out of town.

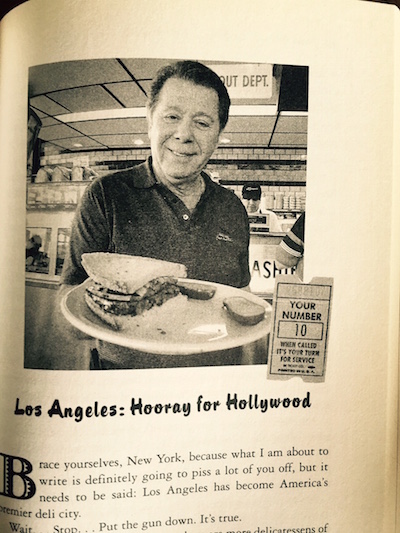

Sax proves entirely accurate in his passionate, entertaining and perceptive homage to the Jewish delicatessen. starting with a glowing chapter on Los Angeles family-run delis with a critical view of that impersonal deli corporation (Jerry’s) sandwiched into it.

Sax proves entirely accurate in his passionate, entertaining and perceptive homage to the Jewish delicatessen. starting with a glowing chapter on Los Angeles family-run delis with a critical view of that impersonal deli corporation (Jerry’s) sandwiched into it.

Brent’s has a starring role (yes!), and Sax uses L.A. rye bread as a standard in this lively road trip that explores and evaluates deli life in the big cities, such as New York, Los Angeles, Miami; Montreal and Toronto; the unexpected in Boulder, Salt Lake City and Houston, and historic London, Warsaw and Paris.

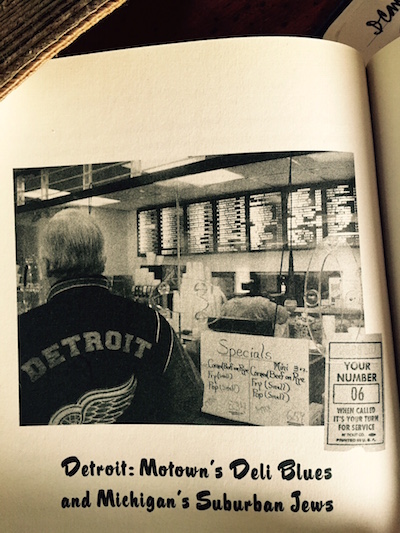

Sax goes so much farther, though, connecting the dots for me from the venerable Lou’s Deli, a treat we lifeguards casually biked ten miles to after work, “now in a dangerous part of Detroit… where business is transacted through a bulletproof Plexiglas window” to award-winning artisanal Zingeman’s Deli in Ann Arbor, created by a fellow University of Michigan graduate.

Sax can sum up, with cultural nuance, the history of Jews in England, Poland or anywhere, otherwise becoming entire chapters of tedious rhetoric in history books. His account of Poles in contemporary delis, vainly attempting to revive traditions lost along with most of the Jewish population during World War II, is memorable, bittersweet and heart-wrenching.

Sax can sum up, with cultural nuance, the history of Jews in England, Poland or anywhere, otherwise becoming entire chapters of tedious rhetoric in history books. His account of Poles in contemporary delis, vainly attempting to revive traditions lost along with most of the Jewish population during World War II, is memorable, bittersweet and heart-wrenching.

A Canadian himself, David traces his own obsession with deli to family. (his grandfather suffered from heart problems and happily died with a corn beef sandwich in his hand). His gives a lively account of the deli competition between Toronto and Montreal and how the scene changed after many Montreal residents, like his parents, relocated to Toronto.

The basis for most of his ratings is clear: quality hand-cut and house-cured meats and bread, and keeping the tradition real. Yet David makes a story in the telling, and tells the story behind the story; bringing to life my own experience at the legendary Schwarz’s (Hebrew Delicatessen) plain wrap, sit in a booth for six-whether-you-know-them-or-not customers in Montreal.

Sax just gets it right every and each first visit, from a detailed, superbly crafted interview with Los Angeles deli maven Al Langer, of the hand-cut meat and finest rye bread toasted gently on one side, Langer’s deli, just before he passed away. It justifies my praise of the place which originally fell on the deaf ears of L.A. “writers” for decades until Nora Ephron decreed it the finest sandwich in the world in the NEW YORKER food issue.

So. Sax’s book began as a lament for and memorial to delis, a long way from their start as pushcarts operated by Eastern European immigrants on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. You only have to think of the calories and cholesterol in this health-conscious culture! But he surprisingly discovered a hardy and evolving and growing, if struggling, deli culture. He concedes that “a new breed of deli” can “bring the Jewish delicatessen into the twenty-first century, while staying faithful to the flavors of the nineteenth.”

So. Sax’s book began as a lament for and memorial to delis, a long way from their start as pushcarts operated by Eastern European immigrants on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. You only have to think of the calories and cholesterol in this health-conscious culture! But he surprisingly discovered a hardy and evolving and growing, if struggling, deli culture. He concedes that “a new breed of deli” can “bring the Jewish delicatessen into the twenty-first century, while staying faithful to the flavors of the nineteenth.”

I open the book at random. Sax is recounting the reaction of New Yorkers (“by far the most traditional, the most stubborn, the most resistant to change”) to artisanal deli owners elsewhere. “‘That would never work here,” they’d tell me with a scoff. ‘You can’t cure stuff yourself. It’s too expensive. It’s impossible.’ But I knew it was only a matter of time before the deli revolution made landfall in New York. And last summer… I met the man who would make it happen. Noah Bernamoff was 27 at the time, a Montreal suburban Jew with fat sideburns, whose previous job was bassist.”

What didn’t I like about “Save the Deli?”? There were not enough photos, and no mention of a TV series made from the book. And happily, Jerry’s Deli was left out.

Gerry Furth-Sides

Gerry Furth-Sides  Barbara Hansen

Barbara Hansen  Chef-owner Alain Cohen

Chef-owner Alain Cohen  Roberta Deen

Roberta Deen  Jose Martinez

Jose Martinez  Nivedita Basu

Nivedita Basu