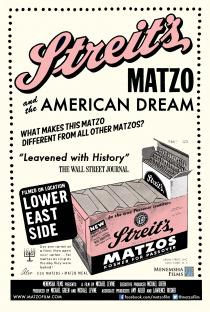

STREIT’S: MATZO AND THE AMERICAN DREAM film

(Gerry Furth-Sides) The historic Laemmle Theatres is pleased to present STREIT’S: MATZO AND THE AMERICAN DREAM, Michael Levine’s film about the historic New York company. The film opens Wednesday, April 20, ushering in passover this year (see details below). The story unfolds in an engaging and loving manner by the family who still head up the company, several of the workers — albeit once the plot is laid, there is a lot of repetition. Insightful urban geographer, Elissa Sampson, places STREIT’s in context to the changing urban dynamics of New York City in such a marvelous, measured manner that it alone is worth “the price of admission.” Director Michael Levine respectfully steps back to allow the story to present itself, from the first time we step into a tour of school children led by an orthodox Jewish elder in the century-old building.

buildings on Irvington Street leftover from the great migration of the previous century – when the lower east side population was more dense than Calcutta, India. The complex, ancient machinery is also a tangle in the four-building factory — “shoots and ladders” as one owner describes it.

buildings on Irvington Street leftover from the great migration of the previous century – when the lower east side population was more dense than Calcutta, India. The complex, ancient machinery is also a tangle in the four-building factory — “shoots and ladders” as one owner describes it. credit, but so too is the “time warp” machinery. Matzo moves along a conveyer belt of creaky baskets as it cools and travels to another level of the building while two rabbis ensure that kosher standards are upheld.

credit, but so too is the “time warp” machinery. Matzo moves along a conveyer belt of creaky baskets as it cools and travels to another level of the building while two rabbis ensure that kosher standards are upheld. Anthony began working at the Streit’s factory in 1983 at the age of 19. Having grown up on the Lower East Side, he was summoned to work by then-owner Jack Streit, who saw him passing by on Rivington Street and called out “hey Italian kid, you want a job?!” Anthony (who is Puerto Rican) was at Streit’s from that day forward, all of whom he considers a “second family,” Many Streit’s employees share similar stories – neighborhood kids who found an unexpected career baking matzo.

Anthony began working at the Streit’s factory in 1983 at the age of 19. Having grown up on the Lower East Side, he was summoned to work by then-owner Jack Streit, who saw him passing by on Rivington Street and called out “hey Italian kid, you want a job?!” Anthony (who is Puerto Rican) was at Streit’s from that day forward, all of whom he considers a “second family,” Many Streit’s employees share similar stories – neighborhood kids who found an unexpected career baking matzo.Echoing Sampson’s thoughts, Anthony stares over the river and muses that everything in New York “has a price. Only the Brooklyn Bridge and The Statue of Liberty – maybe- do not. Is there opportunity for me in another direction? No. no.. no… its do or die. That’s what the eastside is all about now…. There’s no more American dream. No. There’s only the reality. It’s way too late to go back now. It this change good for me? This change is a good thing for me – if Streit’s remains here. If not a good thing if it moves on.”Last fall, after years of deliberation (and failing machinery), the family moved their factory to Rockland County. “Like snowflakes, no two matzos are the same,” we are assured. They did not say anything about the New York water.

“Streit’s stood a living lineage to the Lower East Side’s immigrant past. Dozens of workers buzzed around the ancient machinery, as old as the factory itself, while rabbis kept careful watch, ensuring that each batch met the strictest standards. The owners – the great-grandsons and great-great- grandson of founder Aron Streit – sat behind the desks of their ancestors, holding tight to their family tradition and heritage, despite the obvious challenges of operating a factory out of tenement buildings in the 21st century.

“When I began filming, neither I nor the Streit family could have envisioned that by the time of the film’s release, the factory would leave its Lower East Side home. Suddenly and unexpectedly, the film became not only a document of the family’s history, but a chronicle of the family’s struggle to make the most daunting decision of their lives.

“As a Lower East Side resident who has seen so many family-owned businesses depart in the face of a changing neighborhood, the loss of the Streit’s factory is an emotional one for me, and I know it is even more so for the Streit family and the workers at the factory. However, I also have tremendous admiration for their decision to continue the family business.

“Streit’s may no longer be baking on the Lower East Side, but their legacy there will not be forgotten, and their commitments to community, their workers, and to the matzos they bake will continue in Rockland County.

“I believe that, now more than ever, it is essential that this story be told, not only to preserve the history and legacy of the factory, the Streit family, and the workers there, but to draw attention to difficult choices facing family-owned businesses nationwide.

Elissa Sampson’s words continue to ring in my ears, in my city, in describing the gentrification of the city. “Whether you call it mom or pop shops shop or smaller businesses , or even larger ones like Streits, getting people to feel comfortable in terms of staying in place is critical because staying in place is really the battle about belonging and diversity. Once that diversity is gone, it becomes homogenous, it becomes just another franchise, it becomes another superstore. We see new buildings going up and old buildings coming down. We see communities that don’t know if they still belong. And that sense of belonging is extremely important because losing that sense of belonging disassociates you from everything.”

Gerry Furth-Sides

Gerry Furth-Sides  Barbara Hansen

Barbara Hansen  Chef-owner Alain Cohen

Chef-owner Alain Cohen  Roberta Deen

Roberta Deen  Jose Martinez

Jose Martinez  Nivedita Basu

Nivedita Basu