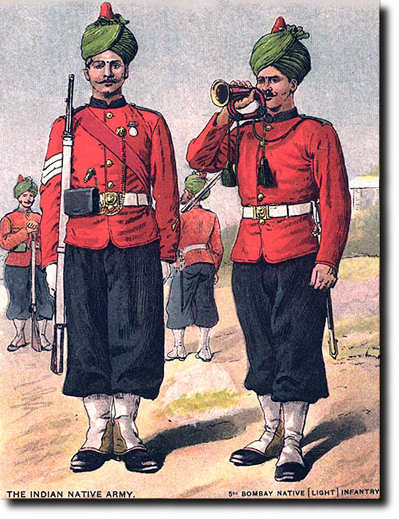

(Gerry Furth-Sides) When French soldiers returned to Paris after their North African occupation they brought cous cous recipes with them, leading to a proliferation of successful Paris cafes featuring the dish. When Brits returned from their posts during the long British rule, known as “the Raj,” whether as merchants, soldiers or administrators, they brought more than favorites dishes back home with them. Brits had developed a love affair with all of Indian cuisine –usually with a dash or more of their own familiar flavors blended into them. And so they brought back what came to be known as Anglo-Indian Cuisine, or affectionally as, “bugle food.” Bombay Bugle is the first to bring it to LA.

First up is Fish N Chips. White fish lightly coated in a batter infused with IPA (Indian Pale Ale) takes on a more British stance than the Indian version sold In India, which uses Indian stout. Indian seasonings are also added, such as oregano. It is served with homemade tartar sauce.

Next up is a wildly popular Mumbai street food, Bombay Frankies. Vendors first starting making them as the solution to a way to serve food without plates. Thick, egg-washed, naans act like a tortilla wrap around a flavorful and textured bouquet of julienned veggies, sometimes joined by chicken cutlets. Known as “Mumbai burritos”, the Frankies have been catching on in parts of the US.

Brussels Sprouts, Cauliflower Dumplings are also on the menu. The fragrant, interesting little kick of Indian spices elevate these familiar, common, work-horse crucifers of the mustard family.

A Chicken Wing Basket holds a choice of Roaster paper honey, Chipotle or Tandoori masala dipping sauces.

Brits prove their love of Indian food annually when they vote in Chicken Tikka Masala as one of the top five, if not the top most popular meals in England according to annual polls. And, in fact, this dish was almost accidentally created by an Indian restaurant owner in London. It is an excellent example of the two cultures intertwining.

Still, the roots of this favorite English with curry has as its origins a definite Indian essence. Chicken Tikka Masala can be traced back to the 18th century and the birth of Anglo-Indian cuisine when local British officials actually began mixing ingredients from Indian dishes with ones that they favored from their British favorites.

Initially documented in detail by the English colonel Arthur Robert Kenney-Herbert writing in 1885 to advise the British Raj’s memsahibs what to instruct their Indian cooks to make at home.

And what dishes! Some became so popular that they made their way into the main stream culinary world include chutneys, mulligatawny soup, salted beef tongue, kedgeree, ball curry and fish rissoles.

Best known of all, of course, is Chutney. Again, what is there not to love? Enormously popular from the start, versatile chutney remains a favorite worldwide and adapts to many cuisines. The mixed preparation of fruit, nuts or vegetables is cooked and sweetened but not highly spiced. In the tradition of jam making, an equal amount of refined sugar reacts with the pectin in an equal amount of tart fruit, such as sour apples or rhubarb. The sour note provided by vinegar completes the idea of umami in the spread. Think Major Grey’s Chutney, on the shelves of every supermarket.

Anglo-Indian food made its way into British mainstream dining in the 1930’s by way of a restaurant named Veeraswamy. Others slowly followed until there are literally thousands of them there today.

But even some early restaurants in England, such as the Hindoostane Coffee House, which opened its doors to London diners in 1810, served Anglo-Indian food. The very homey type cooking drew high praise immediately with The Epicure’s Almanack praised it in 1815 with these words, “All the dishes were dressed with curry powder, rice, Cayenne, and the best spices of Arabia. A room was set apart for smoking hookahs with oriental herbs.” This popularity extended soon after into Indian home cookbooks food sharing recipes.

Names of the anglo-Indian dishes, with their whimsical and crisp sound, incorporate both British and regional Indian terms. Pish pash was defined by Hobson-Jobson as “a slop of rice-soup with small pieces of meat in it, much used in the Anglo-Indian nursery”. The name comes from the Persian pash-pash, from pashidan, to break. A version of the dish is given in The Cookery book of Lady Clark of Tillypronie in 1909.

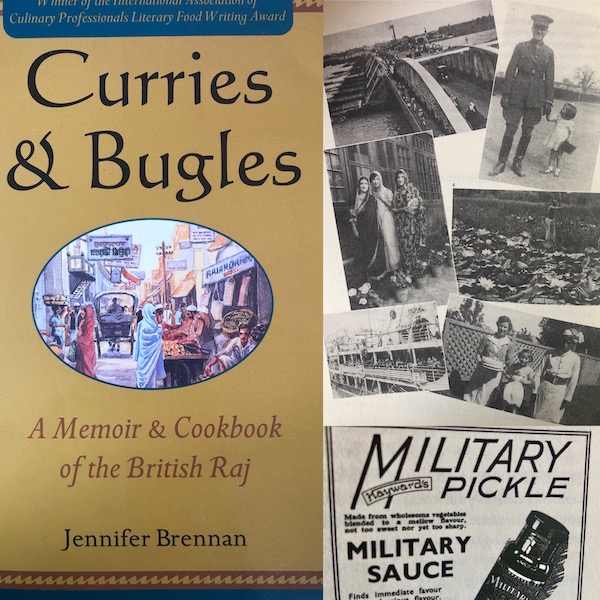

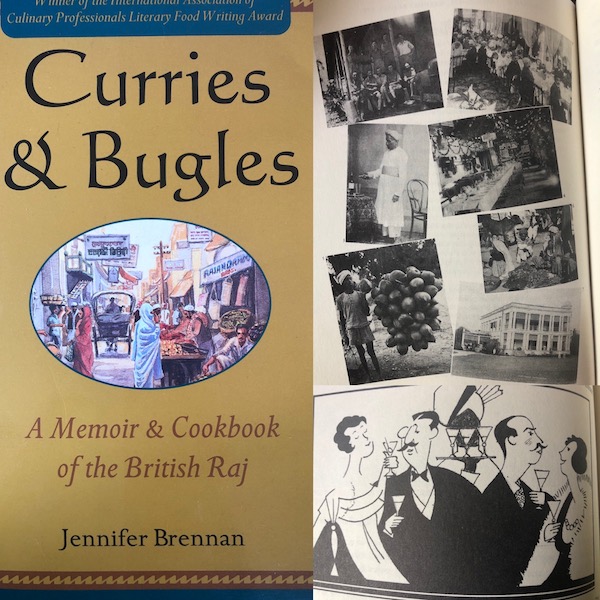

Jennifer Brennan’s beautifully written, Curries & Bugles book (2000) explains Anglo –Indian is still represented by The Regimental Mess remains that remains in “the heart of every military town across England. In her words: “in both countries, those bastions of tradition were erected within the same span of time, and they bear within their bricks and mortar, stones or whitewash, the architectural pride of the Empire and the reverberations of glory immortalized by Rudyard Kipling. …. The regimental Mess of the nineteenth century was almost a secular cathedral.

Gerry Furth-Sides

Gerry Furth-Sides  Barbara Hansen

Barbara Hansen  Chef-owner Alain Cohen

Chef-owner Alain Cohen  Roberta Deen

Roberta Deen  Jose Martinez

Jose Martinez  Nivedita Basu

Nivedita Basu