“Oh, My Papa:” Digging Up Tommy Tang’s Cultural Roots in China

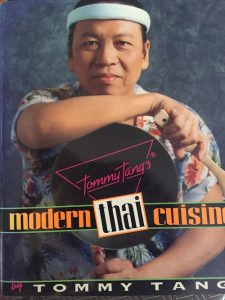

(Gerry Furth-Side) Traveling with Chef TommyTang to film the travel sections of his fourth TV cooking series, Tommy Tang’s Modern Thai Cuisine, aired on PBS nationally, turned out to be a major culinary hunt for the remembered “great noodles” of his youth. This was only a part of the larger quest to document the culinary legacy of his ancient maternal and paternal heritage through the Dai people of southwest Yunnan province, southeast China, northern Thailand (Chang Rei), plus the Cantonese population in the southern China, respectively.

(Gerry Furth-Side) Traveling with Chef TommyTang to film the travel sections of his fourth TV cooking series, Tommy Tang’s Modern Thai Cuisine, aired on PBS nationally, turned out to be a major culinary hunt for the remembered “great noodles” of his youth. This was only a part of the larger quest to document the culinary legacy of his ancient maternal and paternal heritage through the Dai people of southwest Yunnan province, southeast China, northern Thailand (Chang Rei), plus the Cantonese population in the southern China, respectively.

On Tommy’s trip, the connections that were the most impressive were not about the food, but about the food conversations.

We began and ended our journey for the “most authentic ancient noodle” in Guangzhou (Canton) but it was hard to concentrate on the noble noodle we had hunted down on that initial visit to a well-researched out restaurant on the third floor of an massive old office building,

This was because the kitchen, as such, was virtually unrecognizable in the dim light. It was almost impossible to look anywhere but the boards crisscrossing the concrete floor so you could keep your balance and not land on the water underneath, and possibly the remains of what was leftover on diners’ plates from that evening. This was so “genuine” a place that the last letter of an entire new alphabet would be required to designate their level of cleanliness.

So if Tommy said we were on the right track, we were on the right track. The noodles we dined on before the kitchen tour were delicious and, in Tommy’s estimation, quite authentic.

Next stop, Yunnan province, shielded by its breathtaking, if unruly, mountain terrain from outsiders and always considered distinct from the rest of China. Peacefully multi-ethnic, and historically complex, it is also the largest provider of “all the tea in China.”

Capital of all of this fertile territory is Kunming. You get an idea of the contentment and pride of the 2 million residents by the fact they named the town “City of Eternal Spring,” despite 40 degree temperatures during its rainy winter season.

Historically Kunming is famous for its key positioning on the caravan roads to Burma and Europe; Marco Polo stopped there during his 13th century visit to China. He found that the inhabitants enjoying a sophisticated currency but still eating their meat raw, by the way.

The once remote area was formerly considered such a wild outpost by Bejing that political undesirables were exiled there during the Cultural Revolution –until the government realized those exiles preferred not to return to the east. Nevertheless, Red Guards still managed to destroy all but a handful of temples, the old university and a Minorities Institute and theme park, where we saw replicated homes and cultural dances of each province of China, including those of the ancient Thais.

Tommy’s favorite was the Muslin quarter because the cuisine served there is spicier than most southern Chinese food. Endless rows of tiny, offbeat restaurants open day and night in this area truly frequented only by locals offer historic dishes filled with unusual and vibrantly flavored spice combinations, and the fresh produce that is available year-round.

There Tommy found laomien, or Muslin pulled noodles, usually served in soup as one of the best treasures of the quest for noodles. Locals prefer the Muslim mutton stews are the most popular in winter, documented by the sidewalks full of wind-dried beef and mutton carcasses alongside stalls piled high with pita bread and raisins, and huge woks full of roasting coffee beans.

My favorite? The famous pet market, which I was relieved to see addressed itself to the feeding and care of pets rather the selling of them to eat.

Gerry Furth-Sides

Gerry Furth-Sides  Barbara Hansen

Barbara Hansen  Chef-owner Alain Cohen

Chef-owner Alain Cohen  Roberta Deen

Roberta Deen  Jose Martinez

Jose Martinez  Nivedita Basu

Nivedita Basu